Rights to Light Fact Sheet

This Rights to Light fact sheet is intended to provide a basic guide and explanation to those unfamiliar with the subject

Our Rights to Light fact sheet condenses some quite complex matters for the sake of brevity. Please contact us for further detailed advice.

The effect that a right of light has on the development potential of neighbouring land can be serious.

Whether this is for a modest home extension or the construction of a new tower block. The law relating to light is complex.

This Rights to Light fact sheet is no substitute for project specific detailed advice from surveyors experienced with dealing with rights to light issues on a regular basis.

It is intended for property owners on either side of the fence. Where potential developments could be compromised and conversely freehold and lessees potentially threatened with a loss of light as a result of such development.

What is a right to light?

The simplest definition is provided by the Upper Tribunal of the Lands Chamber in its explanatory leaflet for rights to light :

‘If daylight passes across one piece of land to a window or other aperture in a building on another piece of land, the owner of the land with the building on it may eventually acquire a right to light. This is a right to prevent the owner of the first land reducing the amount or passage of light to that window or aperture.’

Most attempts to define a right to light get lost in extending the definition to whether or not the level of light is at an adequate level. Whilst this is a consideration, which we get to below, it doesn’t limit the acquisition of a right to light.

A right to light is an easement. In other words, it is a right acquired by one party (the dominant owner) over someone else’s land (the servient owner).

A right to light is a private legally enforceable right to a minimum level of natural illumination through a ‘defined aperture’. Usually this is a window opening.

Rights to light are separate from the consideration of the impact on daylight & sunlight as part of a planning application.

Rights to light must therefore be considered even if planning permission has been granted.

How is a right of light acquired?

You don’t have an automatic right to light – you have to acquire one.

There are five principal ways to acquire a right to light. By express grant, implied grant, lost modern grant, time immemorial and by Prescription.

There are rare exceptions to acquisition such as transferred rights (from an old building) and Custom of London.

For the purposes of this factsheet we will set out the most common method for acquisition of a right to light.

This is Prescription, or more fully, by the terms of the Prescription Act 1832. The long title of this Act sets out that it was ‘An Act for shortening the time of prescription in certain cases’.

Section 3 of the Prescription Act details specific arrangements for claims to the use of light, as follows :

‘When the access and use of light to and for any dwelling house, workshop, or other building shall have been actually enjoyed therewith for the full period of twenty years without interruption, the right thereto shall be deemed absolute and indefeasible’

A right to light is acquired after 20 years enjoyment ‘without interruption’.

Interruption is stated in section 4 to require a period of one year. As you cannot have a year’s interruption within a 20 year period after 19 years and one day have passed, effectively a right is acquired after the shorter period.

However, you cannot commence legal proceedings to uphold your right until the full 20 years is up.

What does a right to light entitle you to?

A right to light does not give an owner the right to receive the same amount of light forever, or to have no obstruction of any kind to their light.

Instead, it is a right to be left with enough light, the minimal quantity required for the use of the room being served by the ‘defined apertures’ mentioned above.

Much of the understanding of rights to light comes from case law precedents. One such is a judgement in the House of Lords, Colls v Home and Colonial Stores, 1904.

In his judgement, Lord Linley stated that a dominant owner was entitled to :

‘sufficient light according to the ordinary notions of mankind for the comfortable use and enjoyment of his house as a dwelling-house, if it is a dwelling-house, or for the beneficial use and occupation of the house if it is a warehouse, a shop, or other place of business’.

In the same judgement, Lord Davey said that the measure of the quantity of light required was enough for the :

‘ordinary purposes of inhabitancy or business of the tenement according to the ordinary notions of mankind’.

How is the impact of a right to light measured?

If you asked any two people for a definition of the ‘ordinary notions of mankind’ you would almost certainly get two very different answers.

Case law precedents don’t provide clear direction either, as each case comes with its own merits and specific circumstances.

The conduct of the parties is often relevant, as is the use of the affected property.

Having said this, for many years a good initial working rule was the 50/50 principle (55% for residential homes).

This involves calculating the percentage of a room’s area which can receive adequate light. This calculation is undertaken at the working plane, 838.2mm above the finished floor level.

A point on the working plane is considered adequately lit if it can see at least 0.2% of the whole dome of the sky. By tracing a line between those points that receive 0.2% sky factor a contour of the area of a room ‘adequately’ lit can be calculated before and after the construction of a proposed new development.

These calculations are complex and preferably undertaken using specialist computer software.

This involves the creation of a 3-dimensional model of the existing buildings neighbouring a development site as well as a 3D model of the proposed construction.

What remedies are there for an infringement of a right to light?

Infringing a right to light risks Court action. The impacted neighbour is entitled to seek an injunction to have a proposed development reduced in size.

An injunction may also be sought to have all or part of a completed development demolished.

If the loss of light is small and can be given a monetary value a Court may decide to award compensation instead of an injunction.

Rights to Light – Injunction or Compensation?

The way in which a court decides whether to award an injunction or compensation was clarified by Shelfer v City of London Electric Lighting Co in 1895.

In this Appeal Court case four tests were set out to be applied for a Court to award damages instead of an injunction, as follows:

1. Is the injury small?

2. Is it one which can be estimated in money?

3. Would a small monetary payment be an adequate remedy?

4. Would it be oppressive to the defendant to grant an injunction?

If the defendant of a claim is able to demonstrate all of the above, then damages in substitution for an injunction may be given.

However, it is important to note that the default remedy is the grant of an injunction.

In a more recent Supreme Court case, Coventry v Lawrence 2014, there was a suggestion that the courts may be willing to take a more flexible approach to the award of damages in lieu of an injunction.

In this judgement, Lord Neuberger stated :

‘The court’s power to award damages in lieu of an injunction involves a classic exercise of discretion, which should not, as a matter of principle, be fettered; ..as a matter of practical fairness, each case is likely to be so fact-sensitive that any firm guidance is likely to do more harm than good’.

However, judges retain the discretion to award an injunction despite the Supreme Court suggesting otherwise. This was demonstrated by a more recent Court of Appeal judgement, Ottercroft Ltd v Scandia Care, 2016. The case focused heavily on the conduct of the parties.

In awarding an injunction HH Judge Tolson found that the defendant, Dr Rahimian, had :

– Proved to be an untruthful witness

– Acted badly throughout and in an un-neighbourly manner

– Breached an undertaking not to interfere with the claimants’s right of light

This case highlights the fact that the conduct of the parties remains an important aspect in rights to light cases. Failing to engage with a neighbouring owner prior to any infringement is unwise.

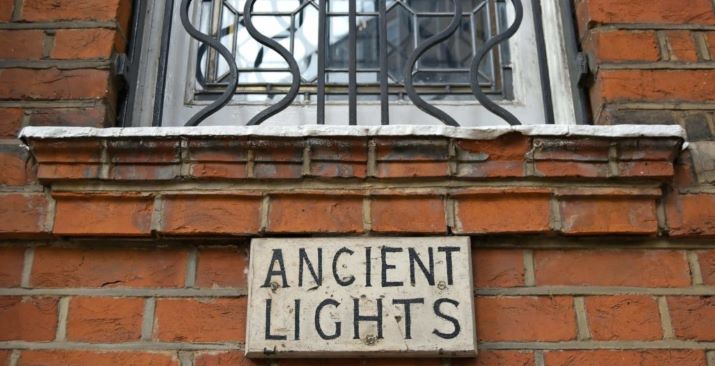

Ancient Lights

Many people think that a sign bearing the words ‘Ancient Lights’ gives some additional protection to a right of light. They also believe that if a window does not have one it will never acquire a right to its full effect.

In fact, such signs mean nothing. They have no value at all. Except perhaps to show that the owner of the building believes he has a right to light and is likely to be strong in its defence.

Some of the best-known examples of Ancient Lights signs are in London. Go and see the back windows of houses on Albemarle Way, in Clerkenwell. They can be seen from the garden of St John Priory Church.

Further Rights to Light Information

We hope you found our explanation of rights to light helpful. Please get in touch for any detailed site specific advice.

The Government also published a rights to light fact sheet as part of a review by the Law Commission.

For clarification of the correct VAT treatment of Rights to Light Compensation, see our recent article. For examples of our work, see our articles on Colindale Gardens redevelopment and Dakota Hotel in Manchester for instance.

With offices in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Bristol, Norwich & Plymouth we provide Rights to Light advice all around the UK.

Contact

For the contact details of a surveyor local to you, see our Birmingham, Bristol, Manchester, Norwich, Plymouth & London Surveyor details.

For advice on rights to light direct from one of our surveyors, please call our Rights to Light Enquiry Line on 020 4534 3138.

If you’d like us to call you, please fill in our Contact Us form and we will call you back.

Link: Contact Us

Team members shown:

- Rebecca Chapman

- Matthew Grant

- Stephen Mealings